Living in Japan: Personal Impressions

January 2016

The Road Less Traveled

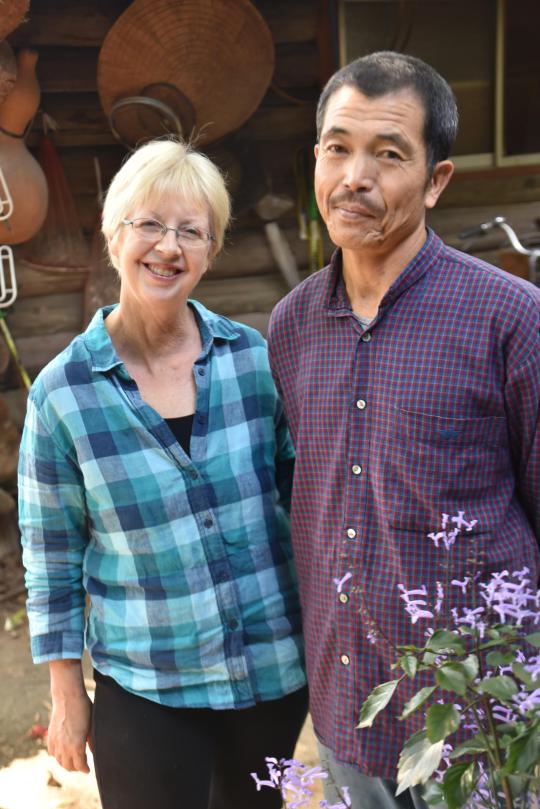

By Wendy Jones Nakanishi

I feel I know Japan and the Japanese well. I am the

beneficiary of circumstances that have made that knowledge possible. I have

lived here for over thirty years: not in some anonymous city but in a rural

area where local families trace back their history for centuries, and customs

have remained largely unchanged in the space of living memory. I am married to

a Japanese farmer and have three biracial sons, and we inhabit a neighborhood

that is like an extended enclave of my husband’s family.

I feel I know Japan and the Japanese well. I am the

beneficiary of circumstances that have made that knowledge possible. I have

lived here for over thirty years: not in some anonymous city but in a rural

area where local families trace back their history for centuries, and customs

have remained largely unchanged in the space of living memory. I am married to

a Japanese farmer and have three biracial sons, and we inhabit a neighborhood

that is like an extended enclave of my husband’s family.

This has granted me the privilege of seeing the

private side of the Japanese: to observe them in their ordinary family lives –

at home, at play. But I also have encountered the professional or public side.

I have been employed full-time since my arrival, at a private Japanese

university. I have attended countless meetings and worked on many committees.

When I am at my college I am treated as a Japanese and expected to act as one.

In this short article I would like to give a few personal

impressions of the Japanese, aware I may be accused of reprehensibly indulging

in stereotypes but willing to take the risk, because I think people who don’t

live here long-term may be interested in what life in Japan for Westerners is

‘really like’. These are generalizations, and there are naturally many

exceptions.

Japan is a

very safe society

It is one thing we all notice and are agreed upon,

‘we’ meaning us Westerners who come to live in this country for any length of

time. Japan is safe! We can leave a wallet on a park bench and it will still be

there an hour later. If it isn’t, it means somebody took it to the nearest police

station. Whether the police have it or it is still on the bench, its contents

will be intact: credit cards, money, everything.

Once I happened to leave a wad of bills, a considerable amount of cash – 50,000 yen, which is over four hundred dollars – on a cash machine in a bank, having just withdrawn that amount to cover my expenses for the following week. It wasn’t until I was in a grocery store half an hour’s drive away that I found my wallet was empty and, horror-stricken, realized what I had done. I apologized to the store cashier, who smiled sympathetically and put my shopping bags under the counter, ready for me to collect when I could pay for them, and rushed back to the bank. My heart sank when I found nothing on the cash machine. Then a bank teller saw me and beckoned to me. Someone had handed in the money. The bank had been able to trace who had withdrawn the cash. The teller had put my cash in an envelope, with my name on it. I had only to offer some form of identification before my weekly shopping money was restored to me.

This feeling of safety and personal security is

pervasive in Japan, especially in a rural area such as mine. I never have that

frisson of fear I used to experience when I was out late at night, walking in a

deserted or unfamiliar neighborhood in America or Europe. I have never suffered

sexual harassment. I don’t count my change when I buy anything. I don’t check that

all our doors are locked before we retire to our bedrooms at night.

I’ll give just one more example, but it is a typical

one. Last year, an Australian friend posted a photograph on his Facebook page.

It showed a thousand-yen note pinned to a sheet of paper wedged conspicuously under

a bicycle tire. The paper contained a handwritten apology to the effect that my

friend’s bicycle had inadvertently been knocked over and its lamp smashed. The

note-writer wanted my friend to use the thousand yen to get the lamp replaced.

This story reflects the value placed upon honesty in

Japanese society. My friend would never have been able to trace who had

accidentally tipped over his bike, yet the individual responsible felt it

incumbent to offer restitution. Also, the thousand-yen note was in plain sight,

perhaps for hours, in a crowded bicycle parking lot next to a busy train

station, but nobody took it.

The Japanese

are a dignified people

This is a matter related to the Japanese emphasis on

principled living. Although it can be tiresome to be stared at as a foreigner,

there is kind of compensation in the fact that we Westerners are confident that

this curiosity will never be accompanied by rude or aggressive behavior.

The majority of us Westerners in Japan work as

language teachers. Although our students tend to be too passive and quiet, we

agree we are lucky to have them. We need spend little time on classroom

management, on keeping order. Sometimes we may encounter students who look

outwardly rebellious, who may even boast garishly dyed hair, ripped clothing or

a pierced ear or two. These students might inspire apprehension, but we soon

find that even these apparently unruly individuals exhibit the same politeness

as their more conventionally clad classmates. The ‘rebels’ sit in meek silence

during our lessons. They bow when they are greeted and smile cheerfully and

acquiesce if they are asked to participate in any classroom activity.

The Japanese have been trained up since babyhood to act

politely, to think of others, and to suppress displays of selfishness. Getting angry

is considered an act of rudeness, of reprehensible immaturity, to be avoided at

all cost. This training in courtesy is invaluable in a densely populated

country such as Japan, with some 70% of its interior so mountainous that the

land is uninhabitable, leaving its many millions of citizens crowded into the

flat coastal areas. It is expedient if not essential that interactions are carefully

orchestrated to lessen stress and to keep potential disruption to a minimum in

the cramped conditions that are a feature of everyday life. Bowing is only a

small part of it.

They act considerately and behave unobtrusively,

habits so deeply ingrained that they are even reflected in their clothes. The

Japanese tend to dress conservatively, favoring, throughout life, variations on

the black and white of the uniforms most wore at primary, junior high and high

school. Yet at the same time they are stylish. The women are often impeccably

dressed. They spend great time and effort on presenting the best appearance in

public possible, considering it a breach of good taste, for example, to leave

home without makeup. Japanese men and women alike keep fit and trim and usually

dye their hair black well into old age. We Westerners here sometimes agree to

feeling scruffy in contrast.

The Japanese often wear white surgical masks in winter

to protect themselves from infection but, even more, to avoid infecting others.

My impression is that in public, they also tend to use their faces as masks,

hiding their true thoughts and feelings behind a bland, agreeable expression. I

used to call it ‘putting on the “scroot”’: the Japanese being inscrutable.

In my first years here, I was often struck by how the smiles

and laughter of Japanese people had meanings I had never before encountered.

Japanese sometimes laugh to cover up a potentially awkward or embarrassing

situation. Similarly, they smile to conceal disappointment or frustration: for

example, when, rushing down a platform to catch a subway train, they arrive at

the door just as it closes. A Westerner might be moved to kick the train as it

speeds away to vent frustration. A Japanese offers a pleasant smile, as if

missing by seconds the train he has rushed to board is a delightful, amusing

experience.

From their earliest years, the Japanese are taught to gaman: silently to endure the unpleasant

and even the unbearable. Children are trained up not to cry out when they fall

or hurt themselves. Women in childbirth are expected not to groan, let alone

scream, even though little or no pain relief is offered. Men offer no complaint,

or not publicly at least, when they are asked to work overtime or on weekends.

But the Japanese are very human! Like everyone else, they

are a deeply emotional people. It is just that they have learned to suppress

and regulate their feelings. Again, circumstances have dictated the necessity

of self-control. Japan is a small, crowded country with few natural resources,

an island nation peculiarly vulnerable to the forces of nature: frequently hit

by typhoons or rocked by earthquakes. Its inhabitants must interact

cooperatively to survive. This has led to the Japanese habit of curbing

egoistic impulses, of putting the needs of the group always before their own.

I am glad to report, however, that Japanese are provided a few opportunities to act

badly. Life would be too unrelentingly stressful if there weren’t a few safety

valves, times or occasions when it’s possible to let off steam without fearing

societal repercussions. Some Japanese men, particularly overworked businessmen,

seem to enjoy getting blindingly drunk and, in such a condition, are excused

any excesses. They can be found sprawled in the early hours of the morning on

station platforms or comatose within empty train carriages. Other stressed-out

Japanese find release in driving, exploiting the anonymity offered by being in

a car to indulge in anger. A Japanese behind the wheel can be as impatient and aggressive

? in other words, as badly behaved ? as any Westerner.

Women are

second-class citizens in Japan

I have presented many positive aspects of Japan and

the Japanese. Here is one that is not so pleasant or agreeable or admirable. Many

Japanese males whom I have observed over the past thirty years seem to believe

that women are inherently inferior to men. It was not so very long ago that

women actually were expected to walk several paces behind any male figure they

were accompanying. As a foreigner with a doctorate, employed as a tenured

member of staff at a university, I am seen as ‘special’ and have been largely

exempt from the discrimination I think Japanese women routinely suffer.

In the small private university where I have worked

since my arrival in this country in the spring of 1984, male professors

outnumber female ones by a ratio of perhaps three or four to one. In the early

years of my employment, I was amazed to find that nearly all the female

professors were dokushin – single,

without children – until a woman working in my department explained that she

had felt she needed to make a choice either to pursue a career or to marry and

have babies. She couldn’t do both. The situation has improved slightly in

recent years, but change occurs only gradually in this country, with its

ancient traditions deeply embedded in the social fabric.

Although a number of equal opportunity laws have been passed in recent years designed to level the playing field for Japanese men and women, Japanese women still are routinely paid less than men and have far more limited career prospects. They are expected to quit full-time jobs after marriage. If they manage to keep working after marrying, they must quit if they become pregnant. Once their children are in school and they try to resume paid employment, they often can find only badly paid so-called part-time work: which might mean they must work as much as forty hours a week but can expect no benefits or insurance or bonuses or pension.

Despite or possibly even because of the restrictions

placed upon them, Japanese women enjoy the longest life expectancy in the

world. I am terribly impressed by their resilience, strength and courage.

Although they may only be allowed to serve tea, answer phones and make

photocopies in a company office, women ‘rule’ in the family environment. The

Japanese husband routinely entrusts his paycheck to his wife. She manages the

household and is responsible for the children, allotting her husband an

allowance each month for his personal expenses.

The northeast corner of the island of Shikoku I

inhabit is farmland: there are rice paddies, plots of vegetables and groves of fruit

trees, and it is an important bonsai-growing center. With the liberalization of

Japan’s agricultural markets in the early 1990s, farming has become less and

less profitable, and nowadays most of the young men belonging to traditional

farming families have had to get salaried employment in offices or factories to

make ends meet. It is their wives who have taken over the daily fieldwork.

Despite the vital role women play in this society,

they are still patronized, still valued for looks instead of brains or ability.

A popular format observed in Japanese television and radio programs, for

example, is the talk show hosted by a man and a woman. The man tends to be

middle-aged or elderly while the woman is young. The man can be undistinguished-looking,

but the woman must be radiantly beautiful. The man usually holds forth at great

length on whatever topic is presently under discussion, and the woman’s

contribution is limited to soft murmurs of assent, to the occasional gasp of

wonderment and admiration at the man’s acuteness, or to bursting into merry

giggles when her co-host condescends to make a joke.

My idea: although it is completely unacceptable that

Japanese women do not enjoy the same social status and employment opportunities

as men, it is because they are so strong that they can appear to be weak. It is

an apparent paradox, but one that is nevertheless true in my own experience.

The Japanese

are very kind

A Japanese friend once told me that I’ve known only

kindness from her compatriots because I’m a foreigner. This woman, whose

husband had an eye operation that went wrong when their son was in

kindergarten, leaving him blind, says she knows from bitter experience that they

are often less than kind to each other. It turns out her ‘friends’ advised her

to leave her husband once he had become disabled.

The Japanese are tough-minded, and I can credit her

assertion. But if you, a Westerner, are thinking of visiting Japan, you may be

assured of being treated with scrupulous politeness. You will never have to tip

taxi drivers or waiters or waitresses, and yet you can always be assured of

impeccable service. You won’t need to count your change after making a

purchase. And it is quite possible that you will benefit from extraordinary

acts of generosity and hospitality.

Soon after my arrival in this country thirty years

ago, I had occasion to board a bus in eastern Shikoku. I had been in the

country several months and had become complacent. I was sure I had boarded the

right bus. It gradually dawned on me that I was wrong, that we were going

somewhere entirely different from my intended destination. At that time, I

spoke very little Japanese. I stumbled up to the driver and held out a paper

with the name of the city I was bound for. He sighed deeply and gestured me

back to my seat before turning around the bus, backtracking several kilometers,

turning down a different road, and depositing me at the stop for the bus I

needed to take.

Incredible! And all the people in the bus understood what was happening. Rather than complaining at the detour, they smiled at me sympathetically, making clucking, tender noises. I felt I had become a child again, one being cared for and guided by kind adults.

Similarly, when my parents visited Japan some years

ago, they were anxious because they knew that after flying into Narita Airport

in Tokyo, they would need to make their way to Haneda Airport, some 30

kilometers across the city, to catch their flight to the city nearest me –

Takamatsu. Working full-time, I was unable to meet them at Narita. I just kept

my fingers crossed that they would somehow find their way.

We needn’t have worried. After disembarking from their

plane at Narita and collecting their luggage, my parents, no doubt looking lost

and helpless, immediately attracted the attention of a middle-aged Japanese

woman who insisted on escorting them across the large, busy airport to the

check-in counter for the Haneda bus. She refused to leave them until she had

made sure they had got the proper tickets and were settled on the bus, their

luggage safely stored below.

This was all effected despite the fact the Japanese

woman spoke little English and, naturally, my parents no Japanese.

Conclusion

There are many wonderful countries in the world inhabited

by admirable people. Japan is one of them. We Westerners who are long-term

residents here often congratulate each other on our good luck in fate’s having

led to our setting up home here. It’s such a civilized society. The buses and trains

run on time. The service in restaurants and shops is exceptional. Japanese culture

calls for people to be well-organized and helpful; for example, once Japan

learned it would host the Olympics in 2020, it began, seemingly overnight, to

provide English signs and even staff at public places, eager to assist any

Westerner in difficulty.

We foreigners will never be wholly accepted in this

homogeneous society. We will always be stared at and, no matter how long we

have lived here, asked where we are from and whether we can use chopsticks.

Still, the advantages far outweigh the disadvantages.

© 2015 by Wendy Jones Nakanishi. All rights reserved.

Wendy Jones Nakanishi has lived in Japan for over thirty years, teaching full-time at a small private college on the rural island of Shikoku. Her academic interests include eighteenth-century English literature, journals, diaries, and the works of Jane Austen, John Ruskin, Virginia Woolf, Iris Murdoch, and modern Japanese novels. Wendy has recently published a murder mystery set in Japan: Imperfect Strangers, under the pen name of ‘Lea O'Harra.’ Enjoy a thrilling story while learning from the author’s deep knowledge of Japanese culture: Imperfect Strangers: An Inspector Inoue Thriller